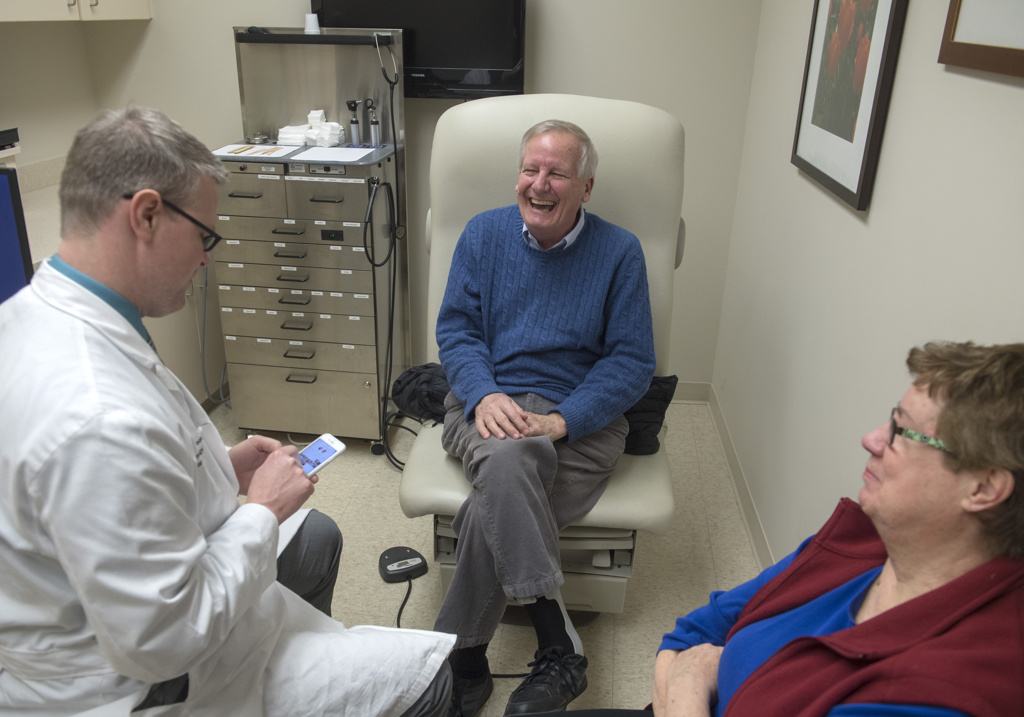

Rob Buitendorp didn’t worry much about the little lump he found on his neck, behind his right ear.

It didn’t hurt, didn’t get in the way. He had no problems swallowing or speaking.

But he had a doctor’s appointment in three weeks, so he decided to ask about it then.

He is so glad he did.

Buitendorp, a 73-year-old retired insurance adjuster, is one of the growing number of people diagnosed with HPV-related throat cancer. And thanks to his quick reaction, he benefited from early detection and treatment.

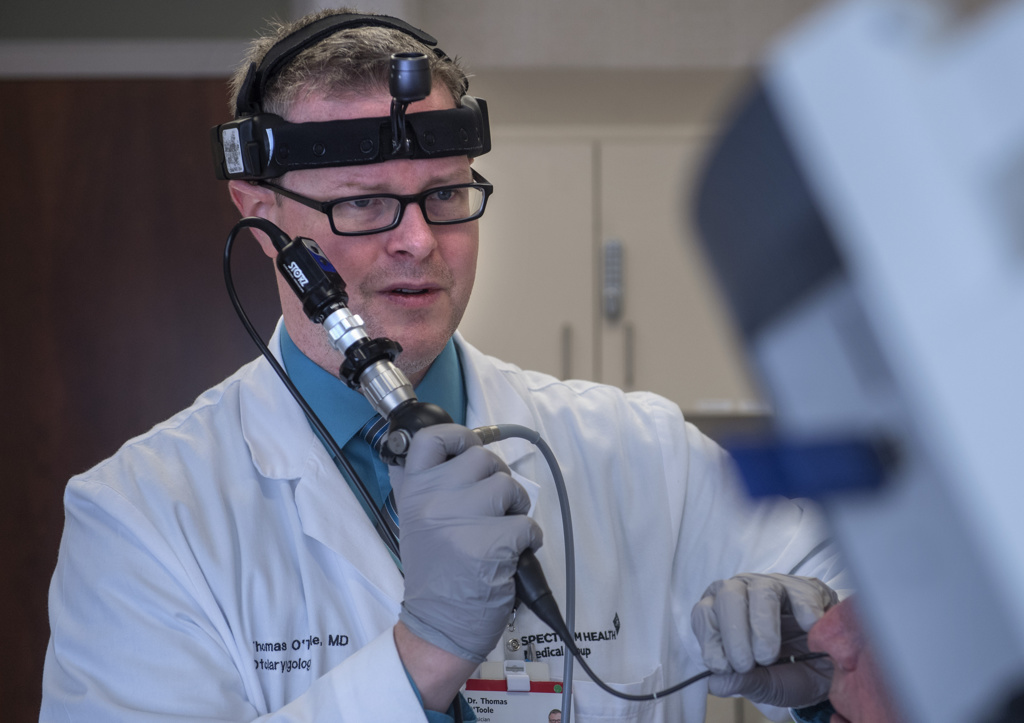

“If the cancer is detected early, then patients are more likely to have a choice of effective cancer treatments,” said Thomas O’Toole, MD, a Spectrum Health head and neck surgical oncologist.

Danger often goes unrecognized

Oropharyngeal cancer—cancer in the back of the throat—strikes more than 18,000 Americans a year, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

It is the most common HPV-associated cancer in the U.S.—more common even than cervical cancer. But the lack of awareness about the disease hampers efforts to combat it.

“This is an epidemic,” Dr. O’Toole said. “It can happen to basically anybody and it’s the scariest thing. It really strikes middle-aged healthy people out of the blue.”

Early detection is key to surviving—or suffering fewer physical effects. But the earliest signs often go unrecognized by patients and, sometimes, even by doctors, Dr. O’Toole said.

The most common early symptom patients notice is a painless bump on the neck. A sore throat is the second most common sign. Too often, people wait months, hoping the problem will go away, before they seek medical care.

“If you have a bump on your neck and it’s been there for more than two weeks, you should go to your doctor, even if you don’t feel any other symptoms,” Dr. O’Toole said. “The quicker we get a diagnosis, the quicker you can get treatment, which is important in terms of improving patients’ survival.”

He recommends the HPV vaccine to prevent the cancer from occurring.

The Food and Drug Administration initially approved the vaccine for youths age 9 to 26 years. But in October 2018, it expanded the approved use of the vaccine to include men and women age 27 to 45 years.

“Because HPV-related cancers may develop decades after exposure to the virus, it may be a while before we see the impact of the vaccine on the incidence of oropharynx cancer,” Dr. O’Toole said.

Cancer rates on the rise

In the 1980s, the medical community began identifying problems with throat cancers related to the human papillomavirus, or HPV.

As smoking became less popular, the incidence of most head and neck cancers declined, as expected. But one form began to show up more often—cancer of the oropharynx.

If you open your mouth and look in a mirror, you see much of oropharynx at the back of your throat. It includes the tonsils, the base of the tongue, soft palate and the back wall of the swallowing passage.

Long before Buitendorp’s diagnosis, lab analysis of oropharynx cancers began to find evidence of a virus in the tumors. They identified HPV in 15 to 20 percent of tumors in the 1980s, and in 80 percent of tumors by 2004.

HPV viruses, which can be sexually transmitted, are common and doctors believe many people have been exposed to them.

“It’s only rare that people end up with cancer from it. It’s something we don’t fully understand—who’s going to develop cancer,” Dr. O’Toole said.

Treatments for cancer of the oropharynx include surgery, chemotherapy and radiation.

“We try to identify what we think is going to be the most effective treatment for the patient with the fewest side effects,” Dr. O’Toole said.

To reduce delays in diagnosis of throat cancer, the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery has developed a clinical practice guideline for evaluation of adult patients with a neck mass, Dr. O’Toole said.

“They recommend that when adult patients have a neck mass for more than two weeks or of uncertain duration without signs of infection, there should be an examination of the upper aerodigestive tract, including the oropharynx and larynx,” he said. “This usually will require referral to an otolaryngologist.”

Dr. O’Toole’s office called and said this is something that should be seen immediately.

When Buitendorp’s internist looked at the lump on his neck in February 2018, he recommended seeing an otolaryngologist. He gave him the phone number for Dr. O’Toole.

When he arrived home, Buitendorp discussed it with his wife, Ruth. He figured he would follow up on the advice—eventually—but he wasn’t worried. The bump was painless.

“In my family, we have a problem with procrastination,” he added.

Fifteen minutes later, a phone call surprised him.

“Dr. O’Toole’s office called and said this is something that should be seen immediately,” he said.

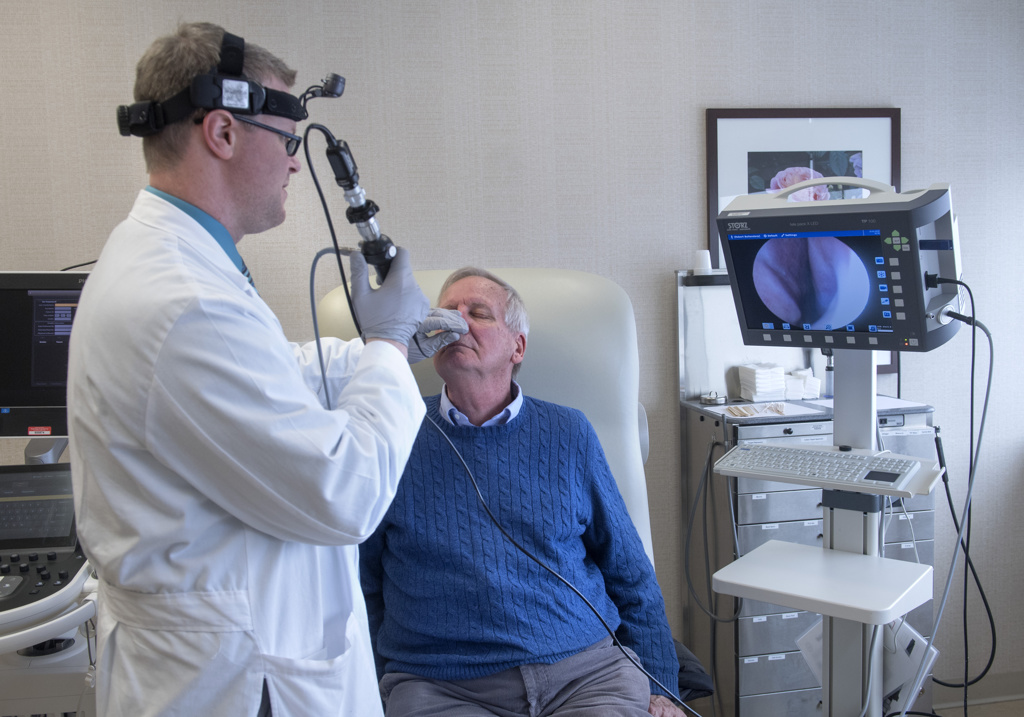

At the first appointment, Dr. O’Toole examined Buitendorp’s throat and showed pictures of a suspicious area on the right tonsil.

“He showed me a growth on the inside that was directly related to the external growth,” Buitendorp said.

Dr. O’Toole performed a fine needle aspiration biopsy in the office. Later, in an operating room, he performed a biopsy of the tonsil, which confirmed an HPV-related cancer.

In March, Buitendorp underwent surgery at Spectrum Health Butterworth Hospital.

Dr. O’Toole performed the operation with the use of the da Vinci robot. The minimally invasive procedure is performed through the mouth. He made only one incision a few inches long in the neck to remove lymph nodes.

The minimally invasive approach makes recovery easier, he said.

A more traditional approach could involve cutting the jaw in half and opening the face like a book. Or a surgeon might make an incision across the neck and take apart the muscles that attach the voice box to the jaw.

“All those things disrupt the muscular attachments,” he said.

He advises patients considering surgery to get an evaluation by a surgeon who can perform a minimally invasive operation.

Dr. O’Toole removed the tumor, which affected the back of the tongue, tonsil and throat. And he removed 66 lymph nodes.

Buitendorp spent five days in the hospital recovering.

“Everything went better than I ever expected,” he said. “I was talking the first day.”

Caught at an early stage

The pathology report showed he had a stage 1 tumor. But because cancer was found in two lymph nodes, he also underwent 30 sessions of radiation therapy at the Spectrum Health Cancer Center at Lemmen-Holton Cancer Pavilion.

After the surgery, Buitendorp didn’t eat for a week. He lost 25 pounds.

In the year since then, he has worked with speech therapists to regain the ability to eat a variety of foods. He takes small bites and eats slowly.

“I’m also getting my taste buds back slowly,” he said.

The post-surgery weight loss is common, Dr. O’Toole said.

“Most people can expect to lose 10 to 20 percent of their body weight,” he said.

Buitendorp knows the cancer or the treatment could have taken a far greater toll without quick treatment.

“This could have been serious if I had not said something to (my doctor),” he said. “That is the key. If you see something wrong, talk to your doctor.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

I have many patients at increased risk of HPV associated cancers.

Unfortunately, many insurance plans do not cover this vaccine for people over 26 years of age.

We need our employers to demand that coverage for HPV vaccines be included.

HPV does not care about your age. It’s about risk, and prevention.

If you already have the virus, can you still get the vaccine to stop it from fueling the cancer? Why can’t the vaccine be given in someone aged 54? Ive just had my second surgery within a year (labia/vulva type).

Hi Pat – Do talk to you physician about this. Generally, they’re seeking to vaccinate people prior to them being exposed to HPV. Best wishes, Cheryl

Wonderful! The quick diagnosis was most important.

Why are our dental providers not involved in the? They should be educating, and possibly even offering the vaccine. Everyone associates HPV with genital cancers, but oropharyngeal cancers are more frequent. Perhaps more would get the vaccine if the approach switched from ‘sex’ to ‘mouth cancer’. We need out dental providers on board!