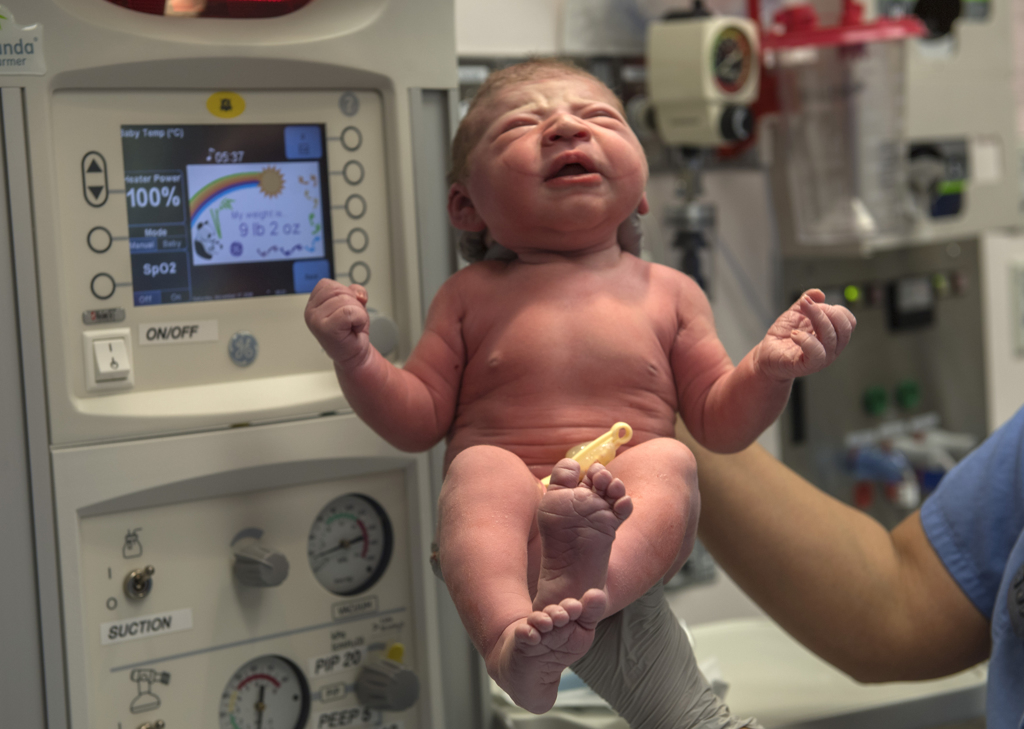

At 3 weeks, Teagan Finnigan already has charmed her parents, learned to smile and even managed to sleep through the night.

In addition to that impressive list of accomplishments, this sweet baby girl just might be a life-saving hero.

A blood donation, taken from her umbilical cord moments after birth, may someday help a child or adult facing a serious illness.

Deciding to donate the cord blood was an easy decision for her mother, Andrea Finnigan. She donated blood for the first time in high school. Since then, she has been committed to making regular blood donations to help others.

During her pregnancy, Andrea could not donate blood. But when she learned about the lifesaving potential of the stem cells found in a baby’s umbilical cord blood, she was eager to be a cord blood donor.

Andrea talked over the decision with her husband, Eric, who readily agreed.

“That’s stem cell-rich blood that can really make a difference in somebody’s diagnosis,” she said. “We are happy to share the wealth. If it’s just going to be thrown away, why not donate it?

“I thought it was a really good opportunity to give back.”

Cord blood really is this miracle that’s out there. And it gets thrown away most of the time.

Cord blood can provide stem cell transplants for people fighting blood cancers, such as leukemia and lymphoma, said Lee Ann Weitekamp, MD, the senior medical director of Versiti, Michigan Blood Center.

It can help patients with sickle cell anemia, as well as cancer patients suffering from side effects of chemotherapy.

Researchers also are investigating its potential to treat other conditions, including cerebral palsy and spinal cord injuries.

‘A miracle’

For Adam Getliff, a cord blood donation made the difference between life and death.

At 15, he fought a particularly challenging form of acute myeloid leukemia. At Spectrum Health Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital, he received a stem cell transplant from a cord blood donor.

Now 22, the young man lives a healthy, active life. He hopes to get a pilot’s license.

He only wishes he could thank the mother and child who provided the cord blood that saved his life.

“It’s crazy to think about somebody selflessly donating that, not knowing if it would ever be used,” he said. “You can only say thank you. You owe them forever. You’d do anything for them.”

His mother, Sarah Getliff, recalled the search for a donor for Adam. None of his three siblings was a match. They found no suitable matches on the national registry.

He received his transplant only because a mother decided to donate her daughter’s cord blood.

“Her gift has given me my son,” Sarah said. “Cord blood really is this miracle that’s out there. And it gets thrown away most of the time.”

Safe for mom and baby

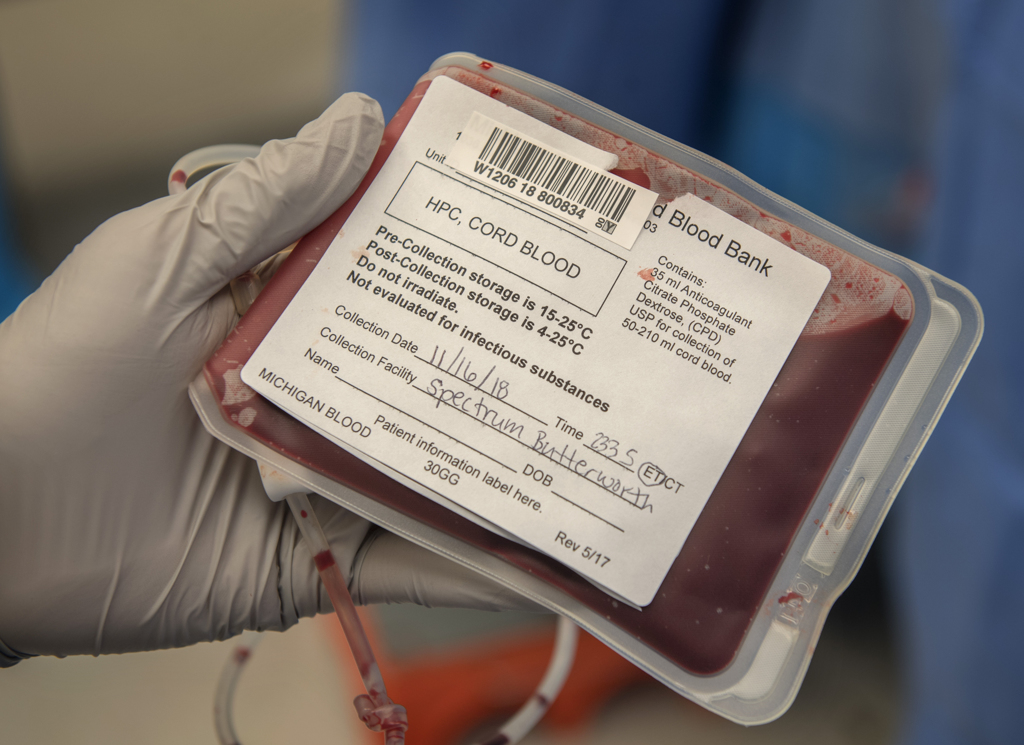

To arrange for a cord blood donation, a woman contacts Michigan Blood, which partners with the Family Birthplace at Spectrum Health Butterworth Hospital in collecting cord blood donations. The organization runs one of 20 public cord blood banks in the U.S. It was the first in Michigan when it opened in 1999.

Michigan Blood has nearly 3,900 cord blood donations frozen and listed with the national marrow donor program. It has provided 215 cord blood donations for transplants. Eighty-five percent of the transplant recipients are in the U.S. The rest were sent to patients around the world.

Worldwide, more than 25,000 patients have received transplants from public cord blood banks, according to Be the Match, the national registry.

Cord blood donations do not interfere with childbirth and do not involve risk or pain for the mother or child, Dr. Weitekamp said.

Andrea recalls little about the moment the cord blood donation occurred. By that point, she had undergone 28 hours of labor and a cesarean section. For her and Eric, the only focus was welcoming their 9-pound, 2-ounce bundle of joy.

Her obstetrician, Robyn Hubbard, MD, handled the cord blood donation, using the sterile collection kit.

After Teagan arrived, Dr. Hubbard waited one minute before clamping and cutting the umbilical cord. This practice, standard for births, has been shown to improve the baby’s blood counts.

Once the cord was cut, but was still attached to the placenta, she cleaned the outside of the cord and placed a needle into the umbilical vein.

“It’s like when you’re donating blood,” Dr. Hubbard said. “It’s pretty easy to do.”

The blood drained by gravity into a collection bag that contained a little anti-coagulant.

“It seemed like a good collection,” Dr. Hubbard said. “We had a decent amount.”

A rich source of stem cells

As a safety measure, Michigan Blood tests a blood sample from the mother as well as the donated cord blood for signs of infectious disease. If all is well, the staff identifies the human leukocyte antigens, or HLA markers, that will be needed to determine whether the donation is a good match for a patient.

Using a sedimenting agent, Michigan Blood isolates the stem cells from the cord blood and freezes them.

The donation—a mere 4 teaspoons of liquid—contains enough stem cells for a life-saving transplant for a child. Adult patients typically need two cord blood donations.

“The beauty of cord blood is, volume for volume, it has way more stem cells in it than a regular blood draw from your arm,” Dr. Weitekamp said. “It is more concentrated than a bone marrow donation or a peripheral blood stem cell donation.”

The stem cells in cord blood also have the advantage of being “a little more naïve,” which makes them more adaptable.

“As you grow, your immune system gets educated,” she said. “Through the thymus, it undergoes a lot of changes as we get older. It gets more sophisticated in how it reacts to challenges like cancer, foreign cells and infectious agents. The beauty of cord blood is that it’s still kind of happy-go-lucky.”

Doctors usually look for a bone marrow donation that matches the patient in all six antigens. But when the stem cells come from cord blood, a match of four antigens may be all that’s needed.

When it comes to choosing a source for a transplant, Dr. Weitekamp said doctors first look for a related adult donor who is a perfect match. If a family member does not match, they try to find a match on the bone marrow donor registry.

In some cases, a patient may receive a half-match transplant from a parent, child or sibling.

For those unable to find a match, a cord blood transplant may be the only option.

Cord blood has often made a difference for patients from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds who are unable to find a matched donor on the national registry. In 2017, 28 percent of umbilical cord transplants were for patients of color, according to Be the Match.

Recently, the use of cord blood donations has dropped about 25 percent, Dr. Weitekamp said. That is, in part, because of the improved success with half-matched transplants.

And it also is due to the fact that stem cells from cord blood tend to take longer to engraft into the patient.

“Although there are fewer total stem cells, they have eight to 10 times more reproductive potential. But it still takes roughly twice as long to get engraftment,” Dr. Weitekamp said.

That leaves a patient vulnerable to infections for a longer time period.

Researchers are looking for ways to expand cord blood stem cells to speed up engraftment.

Andrea hopes that someday, a patient somewhere in the world will receive her baby’s cord blood.

“We are very grateful to have the opportunity to help somebody else who may need it more than us,” she said. Making the donation “was actually a very easy process. I’m just really glad we did it.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

I am pretty sure we donated cord blood from all three of my girls, ages 19, 17 and 10. Is there a way to track if any of the donations were used? My first 2 were delivered at Blodgett and the last at Pennock.

That’s fantastic, Renee! It would indeed be neat to figure out if the cord blood was used. I suggest you contact Michigan Blood at 616.233.8604 and ask. Best wishes to you!