Mike Hensley isn’t the kind of guy who takes no for an answer—not when his life is on the line.

The outdoorsman and former factory worker has grit, and a 20-year struggle with cardiomyopathy and heart failure has only bolstered his will to live.

“You have to wake up in the morning and say, ‘I’m going to live the day, or I’m gonna give up.’ And I’ll never give up,” said Hensley, of Lansing, Michigan. “They’re gonna have to take me kicking and screaming.”

Downhill

Hensley’s heart troubles started in his late 30s, when a viral infection attacked the lower left quadrant of his heart. For the first couple of years, medications kept his symptoms in check.

Then at age 40 he got his first pacemaker, an implanted device that delivers electrical signals to regulate the heartbeat. Hensley’s Lansing-based electrophysiologists adjusted and upgraded the device periodically and kept his heart relatively stable for 15 years. But in 2014 they ran out of solutions.

His heart function and quality of life plummeted.

The time had come to think about heart transplantation, his longtime cardiologist said. So Hensley visited a major heart transplant program—and hit a brick wall.

After an initial evaluation, the program rejected him as a transplant candidate. They told him a secondary medical issue made him ineligible and sent him on his way.

Collaboration

Determined to find a better answer, Hensley and his cardiologist sought a second opinion.

They got it from Michael Dickinson, MD, medical director of the Spectrum Health Richard DeVos Heart and Lung Transplant Program.

Dr. Dickinson, architect of the Advanced Heart Failure Program at Spectrum Health, has cultivated collaborative relationships with cardiologists in a dozen hospitals around the state.

One of these colleagues is Hensley’s cardiologist, Michael Brown, MD, who works at a Lansing hospital and has known Dr. Dickinson for years.

When cardiologists refer their complex, high-risk patients to Spectrum Health, they enter into a partnership, Dr. Dickinson said.

“We can share risk and hand the patients back and forth,” he said. “My job is not to take a patient from Dr. Brown and take over. My job is to make what Dr. Brown does more effective.”

Detailed assessment

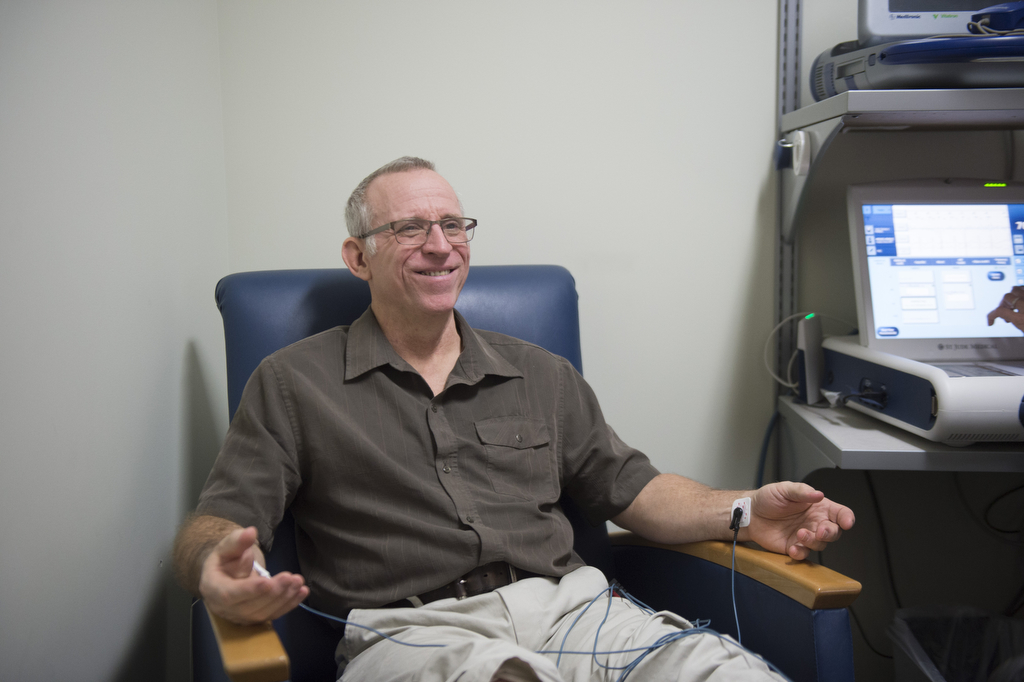

Hensley paid his first visit to Dr. Dickinson in early November 2016.

The doctor sat down with him for a thorough assessment.

“A lot of what we do at the advanced heart failure examinations is slowing things down, dotting the i’s, crossing the t’s,” Dr. Dickinson said.

They’re effectively looking for any subtle targets anyone might have missed.

In Hensley’s case, he found something worth investigating. The functioning of Hensley’s pacemaker troubled him.

My life was so bad. But I got all the right people with all the right knowledge. … I think I’m going to be around a long time.

Dr. Dickinson asked Alfred Albano, MD, a member of the Spectrum Health Medical Group electrophysiology team, to take a closer look at the device’s wires, or leads, which wrap around the heart.

“Dr. Albano was not very happy with what he saw, not happy with how they had placed the leads,” Hensley said.

The doctor suspected Hensley’s downward spiral over the past two years had been caused by problems with two of the leads. It resulted in an imbalanced contraction pattern, which gradually weakened the heart muscle.

Drs. Albano and Dickinson hoped that by fixing Hensley’s pacemaker problems and optimizing his medicines, they could bring him back from the brink and avoid the need for a heart transplant.

“When we do that, we know that we can improve symptoms, actually improve the size and function of the heart and even improve survival,” Dr. Dickinson said. “It works about three-quarters of the time.”

Hensley was all for it.

A week later, he headed to surgery at Spectrum Health Fred and Lena Meijer Heart Center. Dr. Albano inserted a new pacemaker, placed new leads and “got all the walls of the heart working together again,” Dr. Dickinson said.

The result stunned Hensley’s wife, Sue.

“I looked at him during his recovery and within one hour his face was pink again. His hands, his fingernails were pink again,” she said. “We didn’t realize over that two-year time period with that lead in a not-very-good spot, how ashen-colored he’d gotten.”

‘A whole lot better’

Three months after surgery, Hensley said he’s feeling “pretty darn good,” and his doctors hope this solution has reversed the course of his heart failure, making life manageable again.

“Time will tell,” Dr. Dickinson said. “I can’t promise that he won’t end up needing a transplant, but I can promise that if we get there, it isn’t because we didn’t try everything else.”

Looking back, Dr. Dickinson thinks Hensley had “a very good electrophysiologist in Lansing, but he got lost in the details.”

By looking at the big picture, the Spectrum Health team found a way out.

The Hensleys are grateful for their good fortune.

“My life was so bad,” Hensley said. “But I got all the right people with all the right knowledge.”

It made for a remarkable outcome.

“They made my life a whole lot better,” he said.

Although his health issues forced him to retire early, he’s glad he can now fish, travel and spend more time with his children and grandchildren.

“I think I’m going to be around a long time,” he said.

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

Thank you Spectrum for helping my papa as options have run thin for him! You will never understand the love I will always have in my heart for the doctors that have helped keep my papa with me for years to come. We have had the longest journey leading to you all, but I believe in fate and I know we have gone through what we have to get to you. Because of you my papa will happily and healthily be walking me down the aisle in just 2 months to the man I will be spending my life with. Because of you I know my papa will get to know and love my future children and they will know their papa. Thank you for your help! And thank you so much for sharing his story!

This is an incredible story!! I just want to affirm that Dr. Albano is one in a million. I just had an a fib/PVC ablation with Dr. Albano and have never before had the quality and level of care and attentiveness that he gives. So thankful he is part of the team at Meijer Heart Hospital and that this gentleman was able to be helped! Wishing him a long, happy life!