Oh, what a difference a new heart and lungs can make.

Mary Bostwick beams as she cruises around the gym, racking up miles on the treadmill, pedaling a bike and lifting weights.

“I got to be careful,” she says with a laugh as she sits down for a bottle of water. “I think I’m Wonder Woman now.”

The superhero thing certainly agrees with her.

For too many years, Bostwick, 56, of Hersey, Michigan, had to lie low. She missed celebrations. Cancelled appointments. Set only the tiniest of goals.

Just doing laundry knocked her out for the day.

But that was before her big medical milestone.

I swear by everything I am that this gift will not go to waste.

On Oct. 28, 2015, Bostwick became the second patient to receive a combined heart-lung transplant through the Spectrum Health Richard DeVos Heart & Lung Transplant program. It’s a rare event, even on a national scale. Fewer than 20 patients a year receive heart-lung transplants in the U.S., says Reda Girgis, MD, the medical director of Spectrum Health’s lung transplant program.

Gratitude for her new life wells up in Bostwick. It propels her to make the most of each day, whether she’s at the gym or playing with her great granddaughter.

“I am so grateful for this gift,” she says. “I swear by everything I am that this gift will not go to waste.”

Her joyful enthusiasm warms Dr. Girgis’ heart.

“That’s why we do it,” he says. “It’s a lot of fun to see her doing so well.”

Ready to fight

There was a time when Bostwick wasn’t sure she wanted a transplant.

She has coped for decades with lung problems. In 1999, doctors diagnosed her condition as pulmonary arterial hypertension. It causes constriction in the arteries that carry blood from the heart to the lungs. It also strains the right ventricle of the heart and can lead to right heart failure.

Always a high-energy, can-do person, Bostwick struggled to keep up with life. Like an arch villain to her Wonder Woman, pulmonary hypertension zapped her strength and stole her breath.

She had to quit her job as a factory quality control manager. For years, she focused her energy on her family, managing her symptoms with medication.

But by 2011, she felt so weak that even the basic tasks of daily life seemed to take superhero strength.

She and her husband, Sandy, live in a peaceful spot near the Muskegon River in a 925-square-foot home.

“I couldn’t clean it in a day,” she says. “If I took a shower, I couldn’t do laundry. If I vacuumed, swept the floor and mopped, that was it for the day.”

And she never knew when her energy level would bottom out. She had to cancel so many outings that she stopped making plans.

“I was pretty much housebound,” she says.

Afraid of surgery, she resisted any suggestion of a transplant. She worried she might not wake up.

Her thinking began to change in 2014. Her 33-year-old son, Timothy England, shattered the bones in his leg in a serious car accident in Southeast Michigan. As much as Bostwick wanted to rush to the emergency department, she wasn’t healthy enough to make the drive downstate.

As she prayed for her son, she began to see her future in a new light.

“Family is the most important thing in my life,” she says. “I started thinking I have to show my family that you don’t just give up. You fight.

“You fight for everything in your life.”

An experimental device

In September 2014, she became a medical pioneer. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved a one-time emergency use of an experimental device created by Joseph Vettukattil, MD, co-director of the Congenital Heart Center at Spectrum Health Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital.

Dr. Vettukattil implanted the device, called an atrial flow regulator, between the upper chambers of Bostwick’s heart. It reduced the pressure in the right atrium, which in turn improved the blood flow to her body though the shunt created by the device.

Bostwick enjoyed a surge of energy after she received the device. However, the opening eventually closed.

In October 2015, she went on the transplant list.

Her case was complicated by the fact she didn’t just need a pair of lungs. She needed a heart, too. Her right heart was failing. And she had a congenital heart defect―an atrial septal defect, Dr. Girgis says.

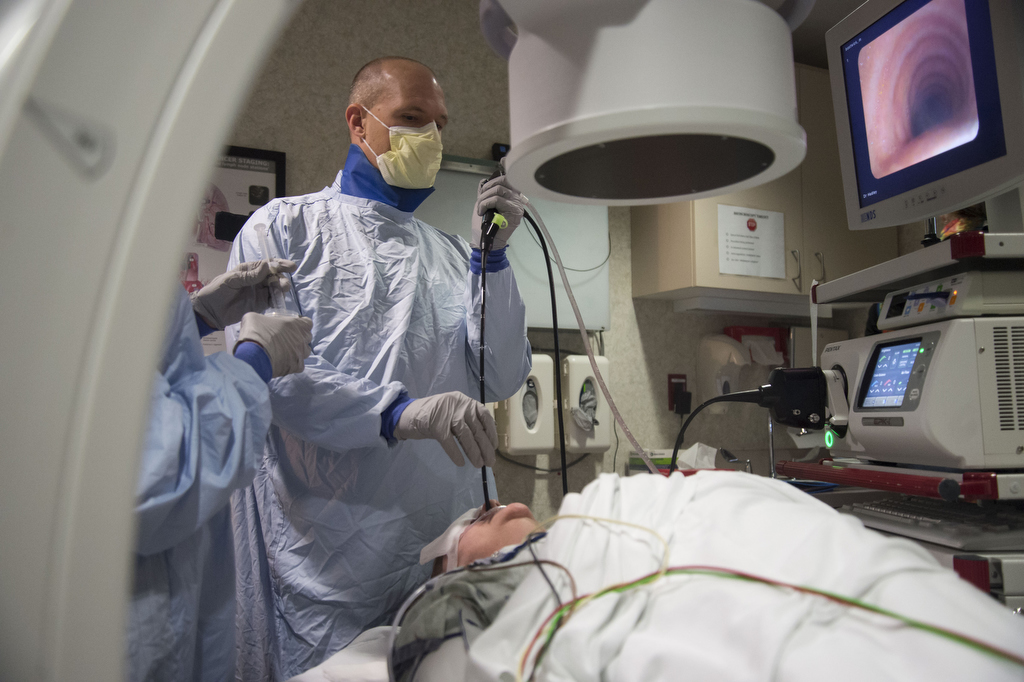

But Bostwick was fortunate that the surgeons at Spectrum Health have the expertise to perform the combined transplant.

“The heart-lung procedure is not something all lung transplant centers offer,” Dr. Girgis says. “You need a surgeon with a particular expertise. Because it’s not done very frequently, there’s not a lot of surgeons who have that experience.”

The lead surgeon for her transplant, Asghar Khaghani, MD, FRCS, began his training in England in 1981, when combined transplants were more common. He estimates he has performed about 200 such transplants.

Prayers for the donor’s family

Fortunately for Bostwick, she had to wait only 2½ weeks once her name went on the transplant list. On a late October 2015 afternoon, she got a call from transplant coordinator Eric Beuker.

“We’ve got a heart and lungs for you,” he said.

I feel like a walking miracle.

Bostwick hurriedly packed a bag with pajamas and a toothbrush.

“I got a little nervous,” she says. “I was running around like a chicken with my head chopped off.”

She and Sandy hopped in the car, and they made the 1.5-hour drive to Grand Rapids, Michigan. She called a few family members to let them know. But mostly, she prayed.

“I prayed for the donor’s family all the way down to the hospital,” she says.

Shortly after midnight, Dr. Khaghani and Theodore Boeve, MD, performed the transplant. They removed her ailing lungs and feeble heart and replaced them with donor organs.

Bostwick doesn’t remember much about her first days of recovery. But one moment sticks with her.

She stood up from her bed, for the first time since her operation. As her new lungs drew breath and her new heart beat within her, she looked around at the room full of doctors and nurses.

“I feel like a walking miracle,” she said.

‘She’s a happier person’

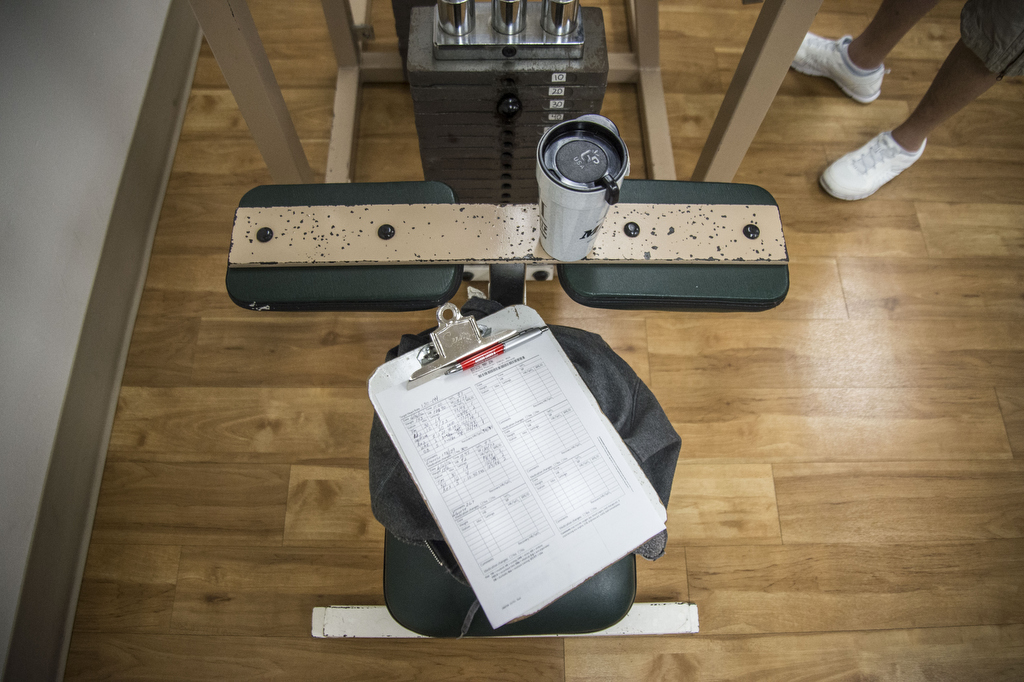

After the transplant, Bostwick began pulmonary rehabilitation at Spectrum Health Big Rapids Hospital, a short drive from home.

She began slowly. All the years of illness had left her short on muscle. But drive and willpower―those she had in abundance.

With twice-weekly workouts, she gradually built stamina. And muscle.

“At first when I came here, I couldn’t do any of this,” she says, on a recent morning as she walks briskly on a treadmill. “I was afraid of this treadmill. I had never been on one before.”

She walked only 10 minutes on her first try. Now she easily walks a half-hour or longer, and at a faster pace. When she hits the weights, she lifts more and does more repetitions.

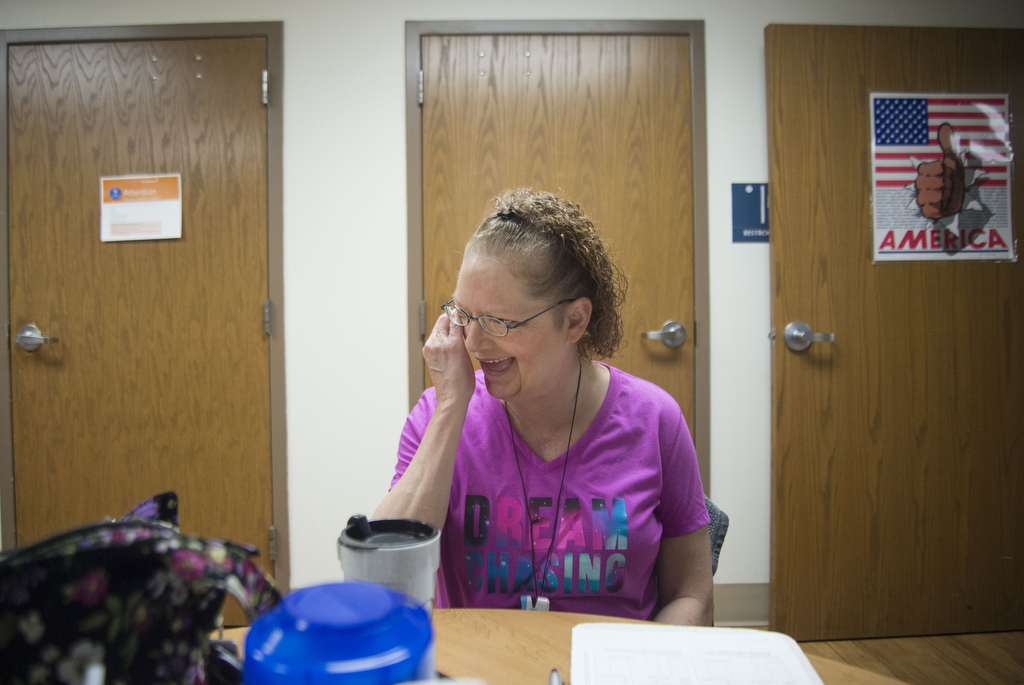

Bostwick returns to the Spectrum Health Fred and Lena Meijer Heart Center for regular checkups.

On a recent visit, she greets Dr. Girgis with a hug. He prints out a report on her lungs and shows it to her with a thumbs-up. Her lung function has risen from about 30 percent to nearly 70 percent.

As Bostwick chats with medical assistant Mary Waclawski, she fills her in on the milestones she has accomplished post-transplant, the real-life moments that bring joy.

“I got to go to a movie with my great granddaughter,” she says. “I’ve been to the beach. I’ve been downstate (visiting family) for two weeks.”

Sandy loves seeing his wife’s transformation.

“She was all skin and bones before the operation,” he says. “Now, she’s got her weight back. She’s active. She’s a happier person.”

The transplant changed Bostwick’s life so profoundly she hopes her story will encourage others who are considering a transplant. And she wants to inspire people to sign up as organ donors.

Someday, she hopes to meet the family of her donor so she can say “thank you” in person, because she knows her new life began with the donor’s gift.

“If I didn’t have a donor,” she says, “I probably wouldn’t be walking this earth today. I truly believe that.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

My wonderful mother in law! A walking miracle!!!!

She is such an inspiration, isn’t she?! I love her joyful attitude. Thanks for reading.

I agree Sue.

It is so wonderful to see and hear of Mary’s success story. She has so much love in her and always doing way more then most people that weren’t sick. God has given her what the family has prayed fo ; her life back. Thank Hod for the surgeons and medicines that give her new life. One tough lady❤️❤️❤️

Another great story about the doctors at Spectrum! God’s coninued blessings on you Mary! (And you wrote another great story Sue!!)

Keep Up the good work with all the support you receive from all of us!