At first it was just a nickname, something his nana called him for fun: Bryar Bear.

Over time, the name has taken on a deeper meaning for the Johnston family of Manton, Michigan, whose 2-year-old son, Bryar, has fought acute myeloid leukemia, a rare form of bone marrow cancer, since he turned 6 months old.

Now “fight like a bear” has become the family’s slogan.

The bear moniker seems to fit this brave little boy, who underwent four months of intense chemotherapy to beat cancer as a baby.

He’d spent just over a year in remission when the leukemia relapsed.

It came as a blow to the gut, just as the family was hitting their stride again, adjusting to life with a new baby in the mix—Bryar’s little brother, Brody.

Bryar Bear would have to be brave once again.

Now he and his mom, Cortney, would return to Spectrum Health Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital to prepare for his next ordeal: a grueling allogeneic bone marrow transplant.

Because there was no family match for Bryar’s bone marrow, his transplant would come from an unrelated donor found through the National Marrow Donor Program.

Preparing for transplantation involved more chemotherapy, with the last round designed to kill off any remaining cancer cells and to condition his body to receive the donor’s marrow.

It’s a brutal process, involving more needle pokes than a toddler should have to endure.

“He really is kind of a little bear—so ‘Don’t poke the bear, because he is very grumpy.’ And he is brave and strong, just like a bear,” Cortney said in October, two months post-transplant.

“Now it’s kind of like his superhero name.”

Ups and downs

Bryar is definitely a hero to the hundreds of family members and friends who follow his “Fight like a bear” Facebook page and who make up the Johnston family’s support group.

“I have a village behind us,” Cortney said. “We have a whole slew of people, whether they’re praying for us, helping us with our kids, sending us toys.”

The family could never do this alone, she said.

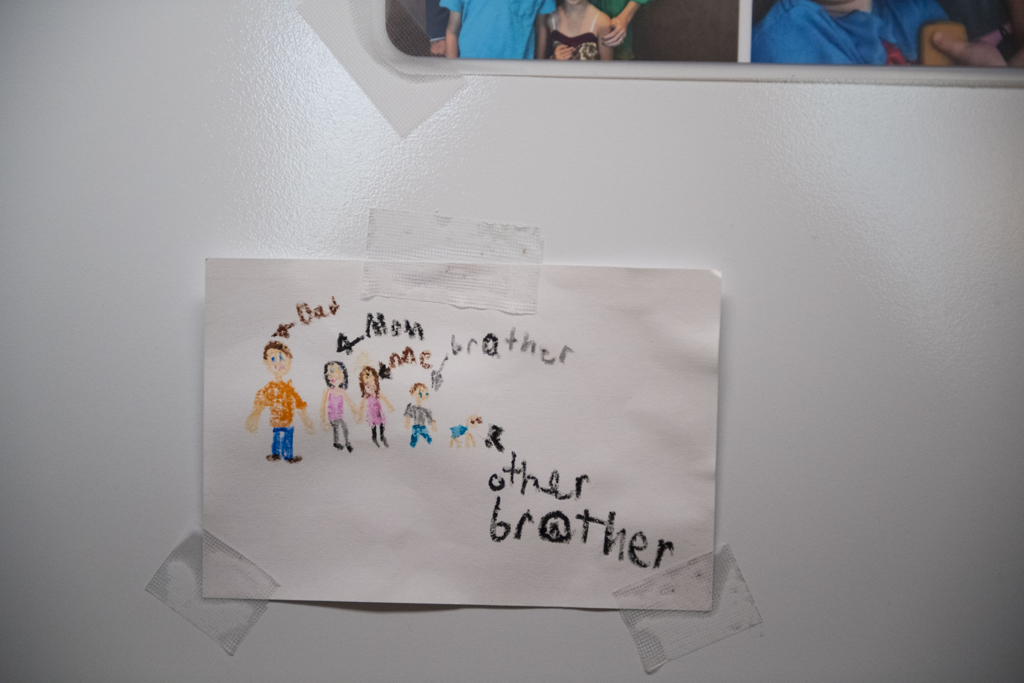

While Cortney and Bryar remain in Grand Rapids, close to the pediatric bone marrow transplant team, the rest of the family—Bryar’s dad, Jeremiah; siblings Sophia, 9, and Brody, almost 1; and the kids’ grandparents—work to maintain a sense of normalcy at home, 100 miles north.

These days, the village is holding its collective breath for Bryar.

His post-transplant recovery has had its ups and downs.

On the upside, Bryar’s post-transplant bone marrow exams looked so good in October that he and his mom left the hospital to stay in the nearby Spectrum Health Renucci Hospitality House.

Staying at “the hotel,” as Bryar calls it, gives them more living space while keeping easy access to the bone marrow transplant clinic at Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital, where Bryar still has frequent appointments.

On the downside, Bryar has faced his share of complications.

In early November, a case of C. diff landed him back in the hospital for a week. Not long after beating that infection and returning to the hospitality house, doctors diagnosed him with adenovirus.

In a healthy person, adenovirus typically causes a common cold, but in a patient with a weakened immune system, it can lead to a more serious infection, said Ulrich Duffner, MD, a pediatric bone marrow transplant specialist.

“It’s a slow process for normal function of the immune system to come back to 100%,” Dr. Duffner said.

“For Bryar, I think it’s much better now already … than directly after transplant. If that adenovirus would have been like two or three weeks after transplant, we would be much more worried.”

Though Bryar’s upper-respiratory symptoms forced a delay of his scheduled bone marrow test—a critical milestone to show whether the cancer remains at bay—he fought off the virus and had the test three weeks later.

The results arrived like an early holiday gift: no leukemia.

The longer Bryar goes without detectable leukemia cells, the better his chances are of beating the cancer, Dr. Duffner said.

“As more and more time goes by, it gets less and less likely that it will ever come back,” he said. “We just all hope and pray that he stays on that track where he is now.”

Daring to dream

No matter how his day is going, Bryar always manages to play.

He may be sick, but he’s still an active, curious kid. A typical boy, Cortney said.

“He’ll just play trucks. He loves playing trucks. He loves construction sites.”

When the Pediatric Oncology Resource Team decorated his hospital room before his transplant, he chose a predictable theme: trucks.

The staff who have cared for him throughout his long journey remark at his resilient spirit.

“Bryar just has an amazing personality,” Dr. Duffner said.

“When he was an inpatient and Bryar had a good day and I myself had a bad day, if you were in his room for a minute to interact with him—it’s just great to see and watch him,” he said about Bryar’s ability to lift up those around him.

“When he’s playing, he always tries to engage you in his play.”

Much of the credit for his resilience belongs to his mom, an upbeat encourager who’s always by his side.

“Even if he doesn’t feel good, I’m like, ‘No, we’re going to play. You’re 2 1/2. Let’s get the Play-Doh out,’” Cortney said.

“Bryar very much has a life still, even though he’s sick.”

While the family waits for Bryar’s future to unfold, Cortney has grabbed hold of reasons to be hopeful. Rather than building a cocoon around themselves, she and her son are making friends with other families on the pediatric oncology floor—people traveling the same path they are on.

And Cortney has allowed herself to dream about the future, about a day when the family can be back together again in their new home up north.

“I’ve been so affected by all of this, in kind of a positive way,” she said. “There’s two ways it can go—either shatter you or build you up.”

She’s chosen to look for “the light in it.”

Grateful for all the love her family has received, she dreams of ways she can use this cancer experience to extend care to others—especially children who don’t have much family support.

“There are kids that don’t have any of that,” Cortney said, referring to the Johnstons’ strong support network.

“Could I be someone that helps these other kids? … That’s the dream. It’s good to have dreams again.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

As a family friend; I am constantly choked up and amazed at all the people involved with this family. From Courtney, that has had to put everything and all others 2nd to Bryar, and has still been able to start a foundation to help others in their family’s position (Fight Like A Bear), to her husband that has done all he can to support his family and still maintain a job and get a new house for the family, to the grandparents that have cared for 10 year old sister and basically raised a healthy baby, to the hundreds of supporters, flooding the hospital with childrens’ plastic Christmas trees, painting Courtney’s new house and babysitting – I tip my hat to all of you❣❣❣

❤️❤️❤️ Love