Kaleb Rietema nestled comfortably in the cupped palms of his doctor’s hands.

But don’t underestimate this tiny, preemie boy.

His entry into the world left his parents and a whole team of caregivers surprised and scrambling to keep up.

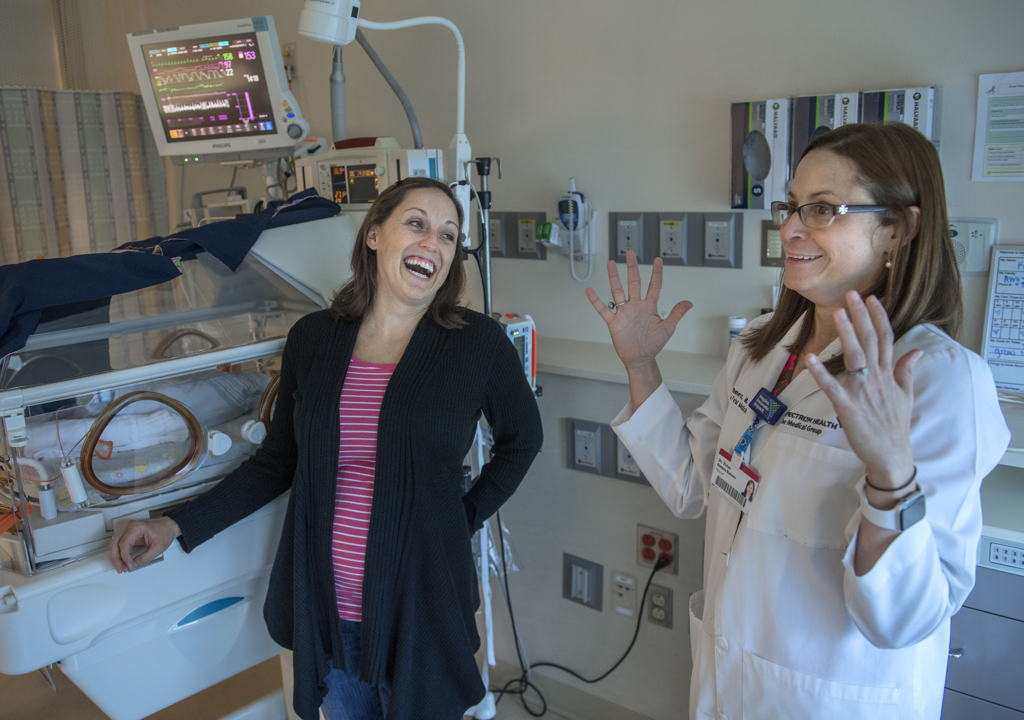

“You gave me gray hair. You have no idea,” said Vivian Romero, MD. She smiled at Kaleb, cradled in her hands in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit at Spectrum Health Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital. “You gave me more wrinkles with your delivery.”

Kaleb gazed at her solemnly. And then a smile flit across his face. His mom and Dr. Romero burst into laughter.

A well-timed surprise—Kaleb already has a reputation for that.

Nothing went as expected on the day of his birth. Well, except Kaleb. He’s just as cute as his parents imagined.

But his delivery day, that’s another story.

‘It escalated so quickly’

Ami and Kurt Rietema, of Hamilton, Michigan, looked forward to the birth of their fourth child. Their three daughters, Kylie, 8, Karis, 6, and Kayla, 18 months, eagerly planned to welcome their first brother.

Because Ami had a large, fast-growing fibroid on her uterus, she received care from the maternal fetal medicine specialists at Spectrum Health.

At 30 weeks, she was admitted to Spectrum Health Butterworth Hospital for monitoring. Contractions began several times, but her doctors were able to stop the preterm labor with medication.

Her medical team planned to deliver the baby by cesarean section for a couple of reasons. In her last delivery, Ami had a classical cesarean section, which involved a vertical incision in the uterus. This left her at greater risk of a uterine rupture if she delivered vaginally.

And the fibroid, now the size of a grapefruit, blocked the cervix and pushed it to the side. It distorted the anatomy so much, her doctors would not be able to tell if she was dilated.

The plan called for delivery at 32 weeks.

One morning in September, Dr. Romero stopped by Ami’s room during rounds. Ami was 31 weeks and six days pregnant.

“She said, ‘You’re doing great,’” Ami recalled. If this continued, they might even be able to wait until 34 weeks to deliver the baby.

The contractions began again that afternoon. And by evening it became clear: This baby could not wait even one more day.

Dr. Romero called together a team for the C-section. Because of the complications involving the fibroid, they needed specialists beyond the usual labor and delivery team. They included a urologist, who could treat any issues with Ami’s bladder and kidneys, and gynecological oncologists who could perform an emergency hysterectomy if necessary.

Neonatal specialists prepared to provide the care a premature baby would need.

“There were a lot of just-in-case people waiting in the wings,” Ami said.

First, a cord. Then, a foot

Before Ami moved to the operating room, another ultrasound was performed. The baby no longer lay sideways, across the fibroid. Now, he lay head up, feet down—in a breech position.

That was one more reason to perform a cesarean. Because of the risk of the head having difficulty coming through the birth canal, doctors in the U.S. deliver nearly all breech babies by C-section.

With the baby’s head under her rib cage, Ami felt she couldn’t bend forward at all. His feet kicked the fibroid, sending pain shooting through her body.

“That’s when it escalated so quickly,” she said. “All of a sudden I got to the point where I felt I couldn’t breathe through the contractions. I could only breathe in. They kept telling me to breathe out, because they were afraid I was going to hyperventilate.”

In the operating room, Ami sat on the table as the anesthesiologist prepared to give her the spinal. But there wasn’t time for that.

“All of a sudden, I felt this explosion,” she recalled. “I think my life is ending right there.

“That sounds so dramatic, but in that moment, I thought, ‘This is it,’ because something came out and it didn’t feel right.”

From the nurses and doctors clustered around her, she heard a voice say, “We have a cord.”

They lay her back on the table.

“I heard someone say, ‘And now we have a foot.”

Two nurses, who stood beside her, said, “You are doing so good. You are doing so good.”

Ami just started to scream. “I felt it was the only thing that was releasing the pain and releasing everything that was going on.”

She didn’t realize that Dr. Romero had not yet entered the operating room.

Michael Strug, DO, a second-year resident in obstetrics and gynecology, delivered the baby.

When Ami felt a “pop,” Dr. Strug feared the fibroid had ruptured and she could be bleeding. But only clear fluid—amniotic fluid—came out.

The appearance of the umbilical cord also raised alarm. When the cord comes out before the baby, the baby can sometimes block the flow of blood through the cord.

One foot emerged. And then the other. Dr. Strug began to guide the rest of the baby out.

“Delivering breech babies (vaginally) is not something we do intentionally, but we are trained to do that,” he said. “We were really lucky that he delivered very easily. The placenta delivered really quickly as well.”

The baby wasn’t breathing. Dr. Strug resuscitated him with a respirator. Kaleb gave the first cry of his life.

“Up until this point, I hadn’t shed one tear. My pain was beyond tears,” Ami said. “Once I heard his little voice, then some tears started coming. I could take a break, because at least he was alive.”

Ami was surprised later to learn that everything had happened in a mere three minutes. She arrived in the operating room at 7:57 p.m. And her son was born at 8 p.m.

“It was the longest three minutes of my life,” Ami said. “It seemed like an eternity.”

Ready for the ‘unroutine’

Dr. Romero hurried through the operating room door, expecting to perform surgery.

“I walk in, and the baby is delivered,” she said. “The placenta is delivered. Mom is fine. And dad is passed out.”

Kurt, dressed in scrubs and waiting for the staff to prepare Ami for surgery, had fainted outside the operating room. A nurse took him to the emergency room, where he quickly recovered.

Dr. Romero’s ultrasound scan of Ami showed she came through the delivery well. Her vital signs were strong. But it took a while to find the cervix because the large fibroid had pushed it to the right side and up high.

“All I could think was, ‘How could she deliver this baby vaginally?’ It’s a mystery,” Dr. Romero said. “I told her the baby essentially used that fibroid as a big slide.”

Kaleb’s birth shows how unpredictable childbirth can be, particularly for pregnancies with complications that require the care of a maternal fetal medicine specialist.

“No matter how much you plan, when the unroutine happens, you have to be ready for it,” she said.

For Dr. Strug, the delivery was “humbling.”

“I think about all the things that could have gone wrong, and I’m thankful that they didn’t,” he said. “I think it will make me a better physician, having experienced that.”

The miracle of birth

At 2 weeks, Kaleb was growing bigger and stronger. He weighed 4 pounds, up a half-pound from his birth weight.

In his room in the NICU, Ami explained how she and Kurt named their son. They drew inspiration from the Biblical story of Caleb, who had faith that God would lead the Israelites into the promised land, even when others doubted and were afraid.

“It says he was wholeheartedly devoted to God and trusted God,” Ami said. “This is just how we see the very beginning of (Kaleb’s) life.

“I believe every birth is a miracle, but this one seemed extra special. It’s exciting to know that no matter what we tried to plan or what worries we had, God was at work with his plan and was in control the whole time. He is so worthy of our wholehearted trust.”

Dr. Romero lifted the little boy from his crib and cuddled him.

“You are such a beautiful baby, my goodness,” she said. “I can’t wait to see what life brings you. You are going to do great things.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

Praising God for Kaleb’s life. God truly can be trusted as his parents demonstrated so well!