The virus is a monster in her mind, a silent stealer of childhood, towering over her life and leeching the fun she used to know.

Lilly Vanden Bosch yearned to breathe free.

A clinical trial in New York City that Lilly recently participated in appears to have slain the monster, leaving it gasping and gurgling for breath. Instead of Lilly dying, it is.

Lilly is getting close. So close to being a regular kid again, to being able to play with friends, eat in restaurants and return to school.

Finding freedom

Diagnosed with severe aplastic anemia at age 7, Lilly faced a rare and raucous battle against a disease that only 2 out of every million people are diagnosed with each year.

She underwent chemotherapy and radiation prior to a November 2015 bone marrow transplant to wipe out her own immune system so it would not battle the cells being introduced from her European donor.

But after a successful transplant, another obstacle stumbled into Lilly’s life—a CMV virus. And it wouldn’t let go.

The CMV virus threatened the function of Lilly’s new bone marrow because of the antiviral medications needed to keep the virus in check. The medicines prevent her bone marrow from developing as it should, which suppresses her immune system.

It grasped her play time with friends and squeezed the life out of it. She couldn’t risk being exposed to their germs. It tunneled into her excursions out of the home. She couldn’t risk being in crowds. She couldn’t shop. Couldn’t swim. Couldn’t eat fresh fruit or drink well water. Couldn’t dine out. Couldn’t go to school.

Too many couldn’ts.

She’s ready to say “I can.”

At the encouragement of Ulrich Duffner, MD, director of clinical services for the Pediatric Blood and Bone Marrow Transplant Program at Spectrum Health Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital, Lilly and her family traveled from their Dorr, Michigan, home to participate in a promising clinical trial at Memorial Sloan Kettering Children’s Hospital.

While in New York City, she got an up-close view of the Statue of Liberty. The shimmering, majestic figure holds special meaning for 10-year-old Lilly. It’s the gatekeeper of the city that gave her freedom—from disease.

After two trips to the Big Apple, the clinical trial treatment appears to have whacked the stubborn CMV virus out of Lilly’s body. Doctors there infused her with T-cells (a type of white blood cell) from a third-party donor.

The clinical trial manipulated those T-cells in the laboratory and trained them to attack the CMV virus.

Sound sci-fi? Perhaps. But it appears to have worked.

“The CMV virus is gone,” said Lilly’s mom, Meg, as they sat in the waiting room on the 10th floor of Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital. “This is what we were hoping for.”

‘She just wants to be a kid’

Dr. Duffner is now in the process of weaning Lilly off her antiviral medications, which should allow Lilly’s internal immune system to function properly.

We’ve always been hopeful, but it just feels more tangible now. It seems like it’s all coming together, like the light at the end of the tunnel.

“We’re very happy with how Lilly looks,” Dr. Duffner said. “We’re confident this is going in the right direction and we can stop more and more of her medications.”

Her counts are coming back to normal, said Aly Abdel-Mageed, MD, section chief for the pediatric blood and bone marrow transplant program at Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital.

“It’s really wonderful to see that. According to what we see, she is turning a corner,” Dr. Abdel-Mageed said. “We hope and pray that will continue.”

Lilly’s three visits to the children’s hospital each week are now down to two, and soon even fewer visits will be necessary.

“It’s hard to believe because it’s been such a long journey,” Meg said. “It’s hard to wrap our minds around it. We’re very hopeful with everything they’ve said, but it’s almost too good to be true.”

It’s a difficult transition for sure. For three-plus years, Lilly has been ill. Now they must learn to see her through the eyes of wellness.

“We haven’t been around people in so long,” Meg said. “It’s kind of overwhelming. We have to get used to just letting her be a kid. She just wants to be a kid, to run around and play.”

Lilly’s hair, which disappeared during her chemotherapy treatments, has grown back full of body and wave. She wants to grow it long again, she says, as she points to her collar bone. Like it used to be.

She wants to go back to St. Stanislaus School in the fall. Like she used to do.

Meg caught herself daydreaming the other day. About normalcy.

“I was daydreaming about going out to eat and going to watch a sunset at the beach,” she said. “We’re looking forward to more and more normalcy.”

Medication schedules haven’t allowed for sunset moments. Or many moments at all not worrying about Lilly’s well-being.

“We’ve always been hopeful, but it just feels more tangible now,” Meg said. “It seems like it’s all coming together, like the light at the end of the tunnel. We had been so focused on the day-to-day, it was overwhelming to think about the future.”

That’s all Lilly is thinking about.

“I’m glad I can think about swimming again … instead of worrying about what my counts will be or if I will have a stomachache today,” Lilly said. “What is the next day going to bring? Am I going to throw up?”

‘Patient a little longer’

After being weighed and measured at a recent appointment, Lilly signed her name on the exam room’s white board. “Lillian.” She added a smiling sunshine. Life is like that for her lately.

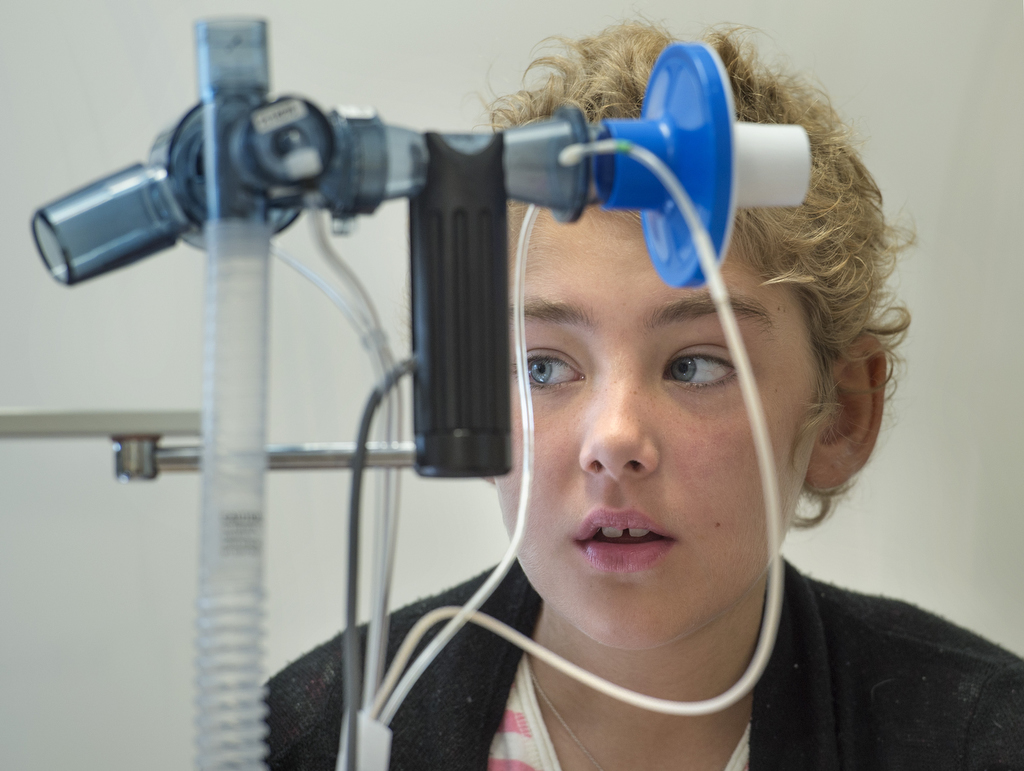

A nurse drew blood from Lilly’s central line. As she waited patiently for the results, Lilly opened up about her past. And her future.

“There were a lot of sick kids there,” Lilly says of her time at the New York children’s hospital. “You think I’m sick? Not even close. I was like the least sick.”

She spoke of her virus in a matter-of-fact way. It’s gone. That’s all that matters now.

“The CMV that I don’t have anymore was basically in my lungs,” Lilly said. “I couldn’t breathe very well. My oxygen level was at 92 when it should have been at 98 or 99. It was hard for me to even go to the bathroom. Now, I’m running around and doing stuff. I have more energy now and I like to do stuff. I like to climb.”

She loved the flight to the Big Apple—on a six-seat aircraft, chartered through Wings of Mercy. She can’t fly on a commercial airline because of her fragile immune system.

“I liked it,” Lilly said, her voice lilting like an updraft. “It felt like a roller coaster.”

Life’s been like that for Lilly, too. But she’s looking far into the future.

“I want to be a hematologist,” she said. “Just ’cause I have a lot of experience and I can relate to the kids that I see. I want to work right here.”

After Lilly cuddled with her mom on the couch, John Younge, PA, entered the room with blood test results.

“Woo-hoo,” Meg yelled. Lilly and her mom cheered and clapped.

“Her numbers are good,” Meg said. “They’re going up a little bit at a time. We would like to get rid of the anti-viral medicine, but we’ll be patient a little longer.”

Younge said he wouldn’t be surprised if that happened soon.

“She’s getting close,” he said. “There’s all kinds of good stuff happening.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

Lilly, we pray that normal will come veerrry soon. You are such a trooper and you have such loving parents. You are very special and God is going to use you to be a blessing to so many others some day. You have inspired me. Blessings! To you and your family.

Wonderful!!

I have been praying for Lily every night & she doesn’t even know me. Marti Newell from her school put her postings on Facebook. I was real taken with this journey she has been. I’m so thrilled with her outcome. I send blessings for all her family. CarolynAbrams