The day started out just fine.

Kim Lautner spent the morning snowmobiling with her boyfriend, Bob Mick, and his family in Bear Lake, Michigan. They returned to his house and she made a salad for lunch.

“He went outside to do something and all of a sudden, I had a severe weight on my chest and a stabbing feeling on my back,” she said. “The pain was unbearable.

“It was very hard to breathe. I couldn’t move. I thought I was having a heart attack.”

Mick rushed her to a local hospital. A CT scan showed a heart attack did not cause her chest pain. Instead, Lautner suffered an aortic dissection—a tear in her largest artery.

The condition, much less common than a heart attack, can also be life-threatening.

And for Lautner, the treatment involved a new device—a system of stents placed during a minimally invasive procedure.

“She is the first person here in the Midwest to have this procedure done,” said Eanas Yassa, MD, a vascular surgeon with Spectrum Health Medical Group. “She was quite lucky to have her dissection when she did, to have the tools available for us to be able to treat her.”

From the local hospital, Lautner was airlifted to Spectrum Health Butterworth Hospital by North Flight Aero Med, a service of Munson Healthcare and Spectrum Health.

“It was a nice day. The sky was blue,” she said. “The staff was so good on the helicopter. They did a good job of managing my pain.”

She went straight to the intensive care unit of the Meijer Heart Center, where tests pinpointed the location of the dissection—or tear—in her aorta. Vascular specialists began treatment.

A tear in the aorta

Of all the blood vessels in our body, the aorta is the mighty Mississippi, a grand, fast-flowing river pumping blood straight from the heart to the rest of the body. Smaller arteries branch off from it, carrying blood to vital organs.

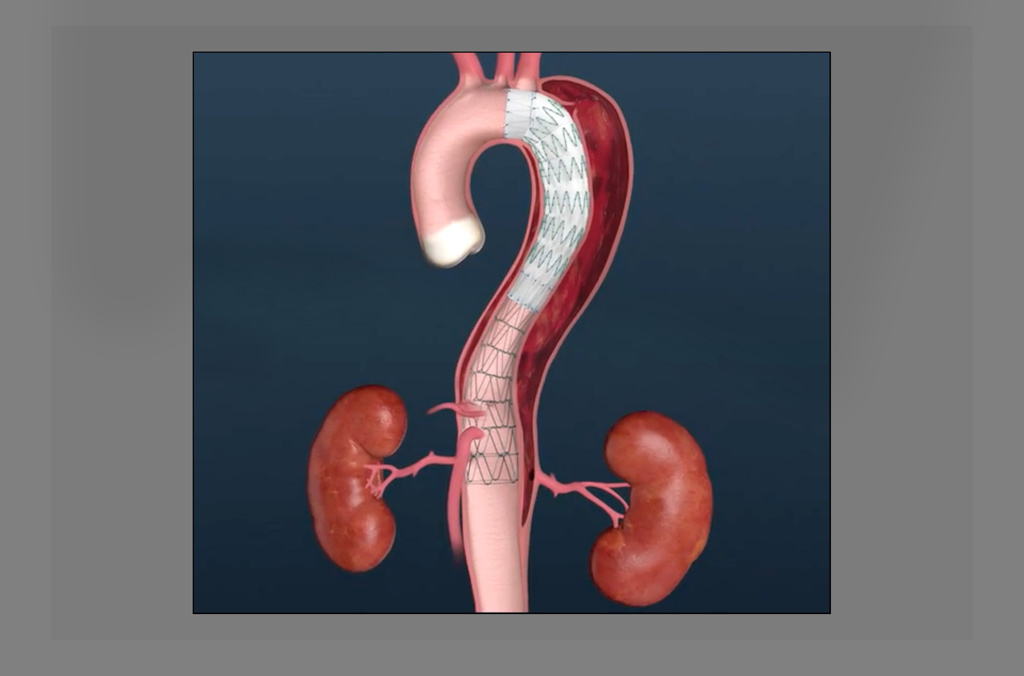

The wall of the aorta consists of three layers. In a dissection, a tear occurs in the inner lining, which allows blood to flow between the inner and middle layers.

In some cases, the blood surging into this opening creates a new, false channel that runs alongside the vessel’s normal channel.

With this double-barreled aorta can come profound risks. It can interrupt blood supply to vital organs or cause a stroke, if not enough blood reaches the brain. Or, most deadly of all, the tear can lead to a complete rupture of the aortic wall.

About 2,000 new cases are reported each year in the U.S., according to the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection.

“They are relatively rare,” Dr. Yassa said. “We see a lot of them here (at the Meijer Heart Center) because we are a big referral center that handles the complicated cases most hospitals don’t have the resources to treat. But they are quite rare in the general population.”

Like Lautner, patients often describe heart attack-like symptoms, such as chest pain and tightness. But with an aortic dissection, the pain is more likely to radiate to the back, Dr. Yassa said.

“Some people actually say it feels like something is tearing,” Dr. Yassa said. “And in both situations (a heart attack and an aortic dissection), there is often just that overwhelming pain and a sense of impending doom.”

Public awareness of the condition rose after actor John Ritter died at the age of 54 of acute aortic dissection in 2003. His widow, Amy Yasbeck, created the John Ritter Foundation for Aortic Health to improve diagnosis and treatment.

Preparing for the repair

The treatment needed for an aortic dissection depends on several factors, including the location of the tear. Some are so complex or immediately life-threatening that they require emergency surgery.

“Thankfully, that wasn’t the case (for Lautner),” Dr. Yassa said. “That allowed us to wait a bit to perform surgery.”

She put Lautner on medication to keep her blood pressure low, while giving time for the inflamed aorta to heal.

After a week in the hospital, Lautner returned to her home near Traverse City, Michigan. She went back to her job as in the Traverse City Clerk’s office, though at reduced hours. And she avoided any activity that could raise her blood pressure.

The low-key lifestyle was quite an adjustment for Lautner, a high-energy 60-year-old who loves the outdoors. She has run a half-dozen marathons, hikes, rides bikes and plays with her grandchildren.

“I’m an all-or-nothing kind of girl,” she said. “A walk for me is not a stroll—give me a three-mile walk.”

About six weeks later, she arrived at Spectrum Health Meijer Heart Center for the operation to repair her aorta.

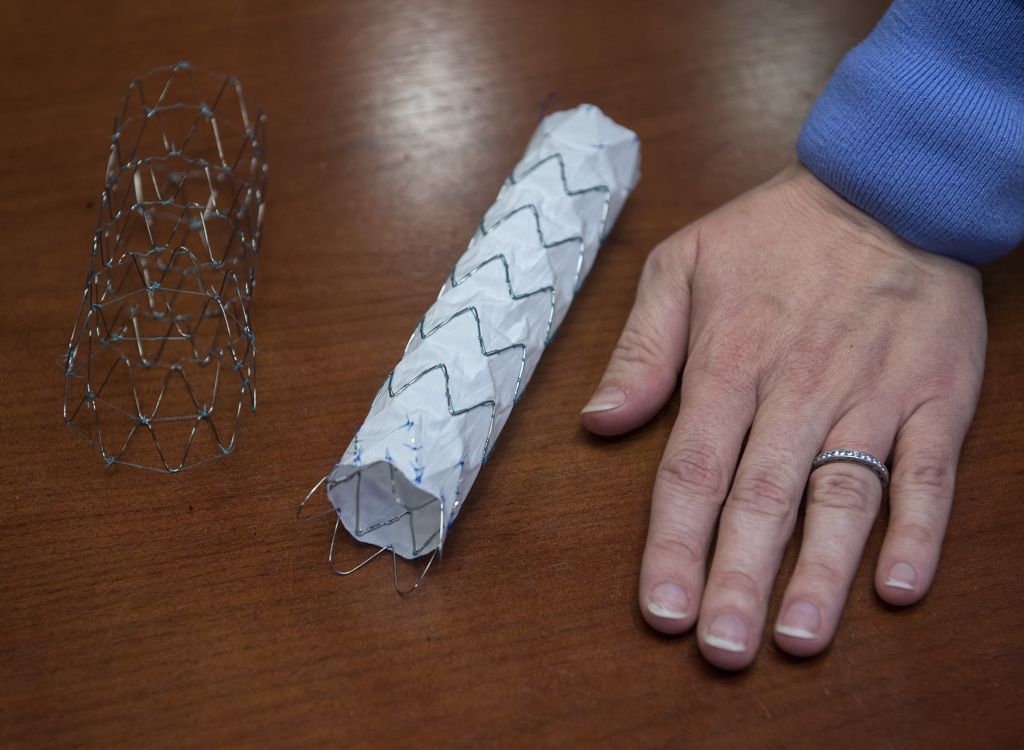

Dr. Yassa performed the procedure using the Zenith Dissection Endovascular System, created by Cook Medical. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved its use in December 2018 and it had been used in only about 20 patients since then.

Dr. Yassa was familiar with the technique because, during her vascular surgery fellowship, she had trained under the surgeon who led the research into the device.

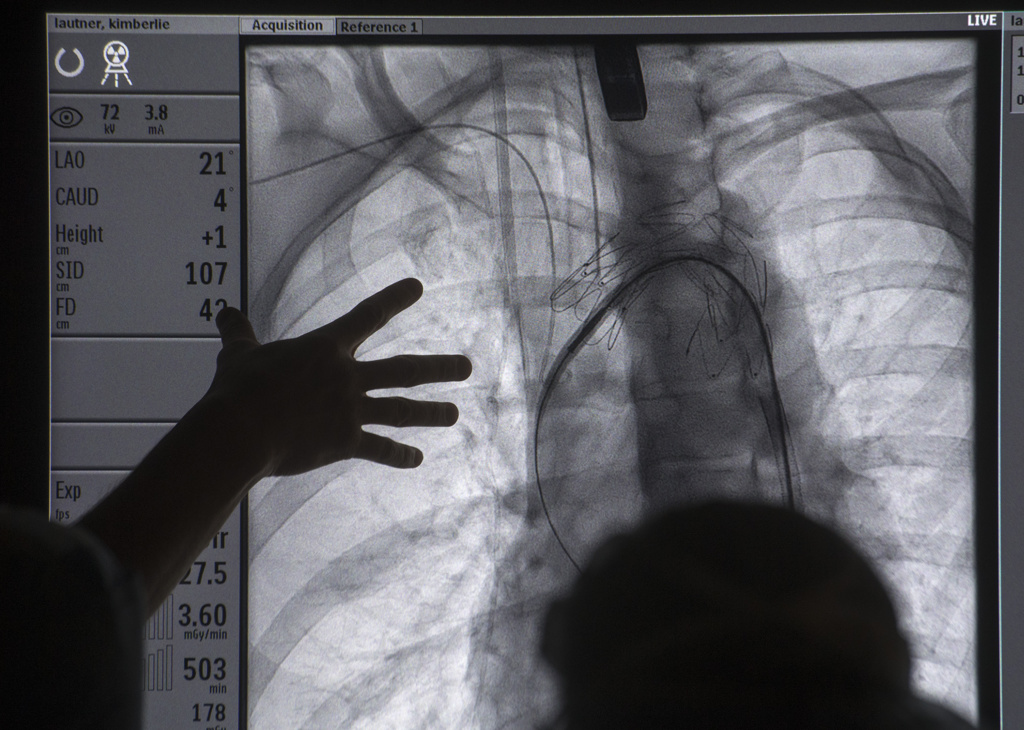

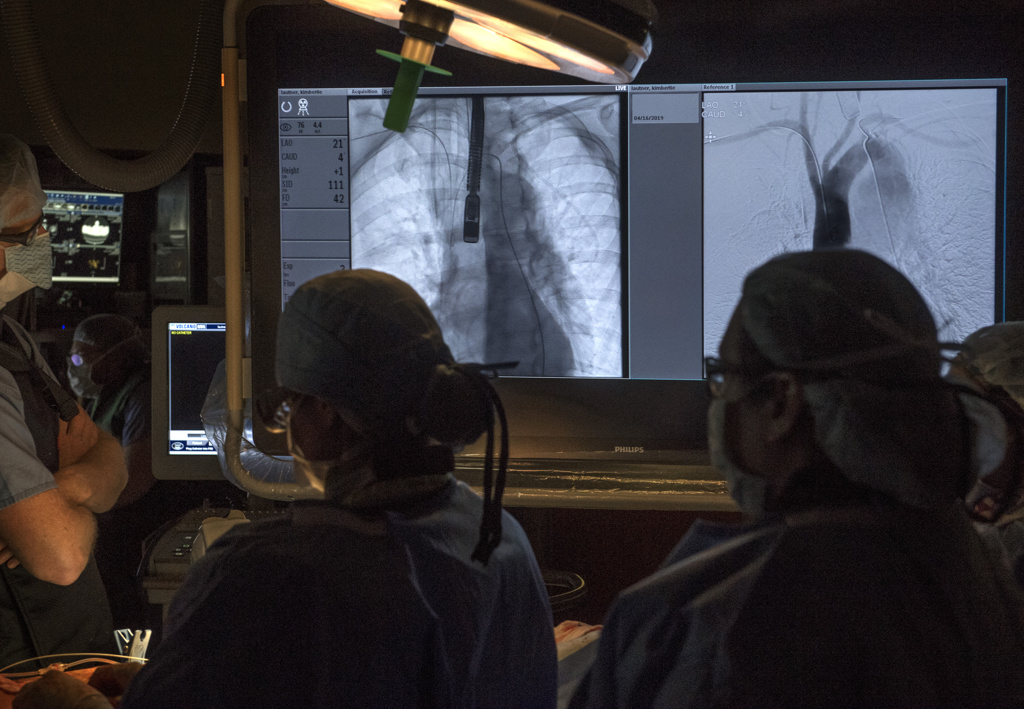

Working through a tiny incision in the groin, Dr. Yassa placed a catheter into Lautner’s artery and threaded it up to the aortic arch, the spot where she had suffered a tear in the blood vessel.

Dr. Yassa first deployed a fabric-covered stent. It expanded in the aorta and blocked the tear, so blood no longer flowed through that gap in between the layers. A second fabric stent was placed next to it, overlapping, to provide additional coverage.

She then placed a series of open mesh stents along the length of the aorta through the chest area. When in place, they expanded, pushing open a wider channel in the aorta.

“The true passageway for her blood was nearly obliterated by the false passageway,” Dr. Yassa said.

These stents were not covered, so blood could continue to flow from the aorta into the smaller arteries that feed the spine and vital organs.

The true passage grows wider

A week after surgery, CT scans showed the stent system was doing its job.

“We have repeat imaging that shows the true passageway for blood has expanded nicely,” Dr. Yassa said. “There’s already some signs the aorta is shutting down the false passageway for blood, at least in the chest area.”

Dr. Yassa plans to closely monitor Lautner and the blood flow in her aorta in the coming months. If all continues to go well, she believes the stent system will reduce the chance Lautner will need surgery on the aorta.

“My hope is that as her aorta remodels, she can come off some of her blood pressure medications and activity restrictions,” she said. “Hopefully, she will be able to get back to a very, very active lifestyle again.”

Taking it easy and accepting help from others may not be in her nature, but Lautner vowed to do both as she recovers.

“This is not going to stop me,” she said. “It might slow me down, so I stop and smell the roses when I’m taking that walk.

“I’m excited. It’s going to be a long road, but at least I’m on my way.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

I’m a friend of Kim’s and she continues to impress many of us with her strength! She’s an amazing woman and inspires us with her strength and positive attitude. I’m so thankful that you and your medical team have helped her so much! Thank you!

Yes, Kim is a rock star!

Thank you Dr. Yassa, her team and the Spectum Health staff that took care of me. Thank you for listening to me, caring, and for the knowledge and strength to take this journey. I can’t say enough about this positive experience. You folks are amazing! The flowers smell beautiful.

Kim, it was wonderful to meet you and spend time with you. I admire your positive attitude and energy! Thank you so much for sharing your story. I hope you enjoy a wonderful northern Michigan summer.

I worked with Dr. Yassa for 3 years and she is an amazing teacher and surgeon! She is kind, compassionate and was always willing to help me with questions. Such an amazing story to share!!

Thank you Kathy! You are missed in our space and I hope you are well.

I had “spontaneous coronary artery dissection” 6 yrs ago. Heart attack symptoms, heart catheterization, stent in my LAD and have been fine ever since. So scary and so thankful for modern day treatment to remedy the problem!

Whew! So glad you’re doing so well, Cris! Best wishes to you!

Mine happen March 19, 2017 I was 53, it felt like a tearing across my chest and horrible feeling of doom I knew something was terribly wrong. I was so lucky to be only be minutes from the Spectrum heart center and their awesome medical staff diagnosed it very quickly and within hours I was in emergency surgery and received a replacement graph on my ascending aorta. I am very lucky to be alive.

We’re so glad to hear you’re doing well, Cindy! Thanks for sharing and for being a Health Beat reader! Cheers, Cheryl

That is wonderful it was caught and repaired. My parents both had aortic aneurysms. Is the something I should be checked for?

Thanks for reading, Debbie. Sorry to hear both your parents had aortic aneurysms. I suggest talking to your doctor about this.

Health Beat ran an article about a family with several members who had that condition. Dr. Robert Cuff, the vascular surgeon interviewed for the story, encouraged screening ultrasounds for siblings and children of those who have an aortic aneurysm.

Check copper potassium levels plastic piping can cause problems.